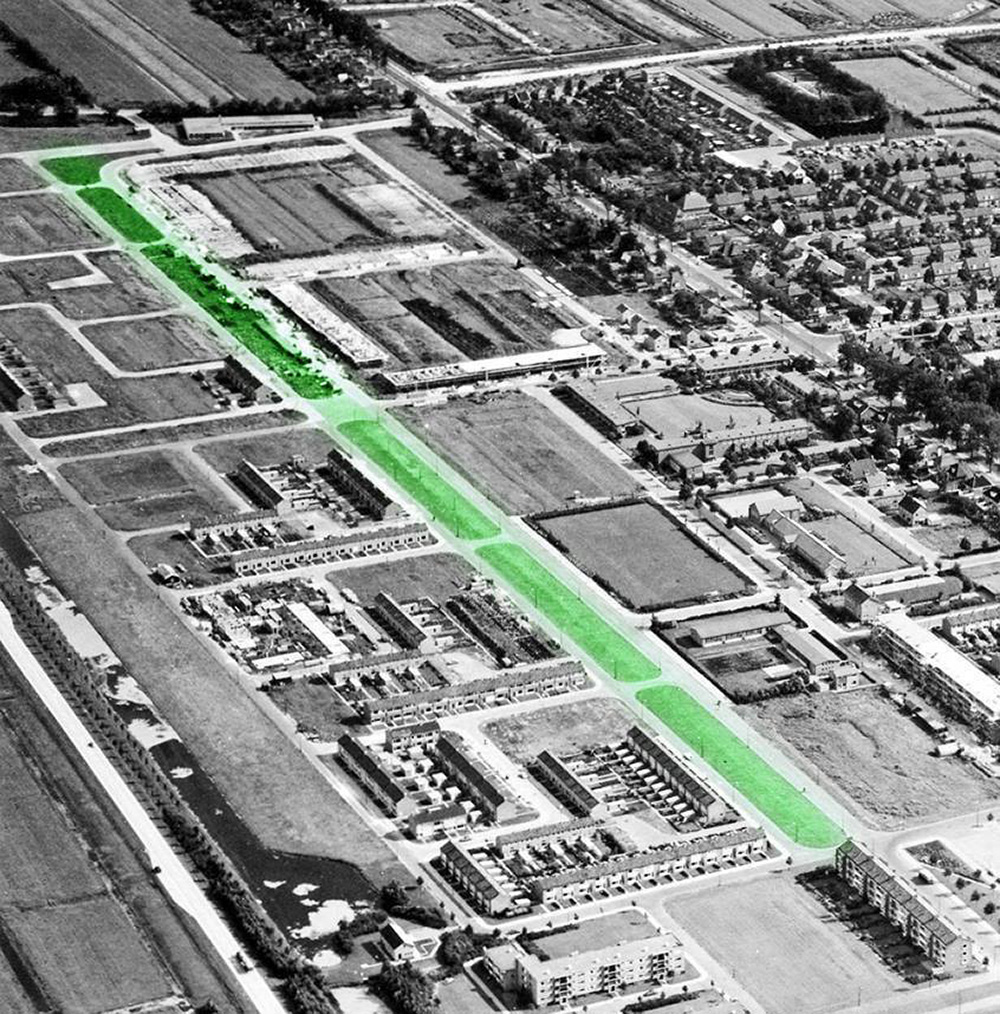

Imagine a medium-sized city that has to expand due to the growing number of inhabitants. A large area of pasture with an agricultural purpose is being prepared for construction, and hundreds of houses and flats are being built. A kilometer long and 20 metre wide strip remains in the middle of the district. Usually an ideal space for sowing grass, paving for footpaths, placing a few trees, shrubs and benches, and with professional maintenance the strip will look exactly the same 50 years later. Only the solitary trees would get bigger.

Now imagine that someone has a different idea and says: let's fill the strip with rubble from demolished buildings in a number of places in order to add complexity to the place. And let's dig big holes where a pond can form. Let's plant dozens of different trees and shrubs more or less randomly and then do next to nothing. We wait and give space time and time space. See how nature reacts on the chaos that was created.

The start of the Le Roy garden in 1966

The start of the Le Roy garden in 1966

1969: Debris of a demolished church as a basis of an eco cathedral.

1969: Debris of a demolished church as a basis of an eco cathedral.

This is what happened in Heerenveen (The Netherlands) in 1966 when Louis Le Roy (1924 - 2012) was given carte blanche by the municipality to design a piece of land according to his ideas. Without making a single drawing, without being able to show anyone an example of what it will become, and without having an end result in mind.

Le Roy had realized that natural processes no longer stand a chance in a city’s public spaces (and also not even outside a city. There is no true wilderness in western Europe to be found). Nature was eliminated everywhere and kept in check with great skill. Control of nature by humans predominated and resulted in a cold, grey living environment. Most of the public gardens had a focus on aesthetics. It had to look nice and had nothing to do with nature. Le Roy considers our approach to nature: “...it must always be remembered that when nature is discussed, it always refers to natural processes, but never nature in its temporary appearance“. What if you switch on nature instead of switching it off? What if you create conditions in which natural processes can develop without leaving people out? After all, we also belong to nature, but have elevated ourselves above it with all the disastrous consequences that entails. Only now are we starting to realise that this attitude will kill us in the end.

Ecotect Le Roy called his projects eco-cathedrals: a combination of eco (nature) and cathedral (culture). Not cathedrals in the religious sense of the word, but because it sometimes took centuries for a cathedral to be finished. Most people who contributed to it knew they would never see the end result. Le Roy knew that a city somehow needs a relationship with nature to survive. By excluding territory from usual urban planning, and allowing creative, natural processes to emerge in time, we can be reminded again that it is pointless and dangerous to keep cutting back on time and just focus on the speed of development.

The project in Heerenveen was started with the intention of allowing local residents to actively participate. The 70’s was not the right time for it. In that time green maintenance in the public space was only done by professional employees of the municipal government. No amateurs were admitted. That is the main reason why Le Roy bought his own peace of land in Mildam. Endlessly, year in, year out, Le Roy stacked millons of used stones, curbs and clinkers (which he got for free from road workers) on his own plot of land. He wanted to show what one human being can achieve, showing how much 1% of humanity could accomplish if building in the same way over time.

His ideas were not only followed in the Netherlands but also in Germany, France, Italy and Austria. He gave lectures throughout Europe and projects were started. The Dokumenta in Kassel invited him to build an eco-cathedral on the site. Money was no object! But Louis declined the order because his building would be demolished after a year. "If I don't get the time, I'm not interested!" was his answer.

The eco-cathedral in Heerenveen is located in the public space that is owned by the municipality. Long-term thinking is not yet commonplace in politics, and there was a chance that the experiment would be stopped after a number of years. To prevent this, a 100 year agreement was signed in 2005 that the eco-cathedral process could continue under the supervision of Stichting TIJD. A hundred years is unique in politics!

Since its inception in 1966, only 55 years have passed. We have only just started.

Peter Wouda, Heerenveen, 2021

Lees het artikel ook op de website van Taking Time